How the Spaces We Design Today Shape a Resilient Tomorrow

For the young generation stepping into architecture, design, engineering or even engaging as aware and responsible citizens, sustainability is no longer a trend or a buzzword. It is a responsibility that directly shapes the future of our cities and communities.

Climate change, rising urban temperatures, extreme weather events, and resource depletion are no longer distant threats. They are present-day realities, influencing how we live, move, work, and interact with our built environment. In this context, architecture and urban design emerge as powerful tools, not just to mitigate damage, but to actively create solutions.

Climate change, rising urban temperatures, extreme weather events, and resource depletion are no longer distant threats. They are present-day realities, influencing how we live, move, work, and interact with our built environment. In this context, architecture and urban design emerge as powerful tools, not just to mitigate damage, but to actively create solutions.

The built environment today accounts for nearly 40% of global energy-related carbon emissions. This statistic alone places architects, planners, designers, engineers, and policymakers at the center of the sustainability movement. Every building constructed today will likely stand for decades, influencing energy consumption, environmental impact, and human well-being far into the future.

In this sense, every design decision matters—from site selection and orientation to material choice, spatial planning, and long-term adaptability. Each choice has the potential to either harm or heal the planet.

In this sense, every design decision matters—from site selection and orientation to material choice, spatial planning, and long-term adaptability. Each choice has the potential to either harm or heal the planet.

Rethinking What Sustainable Architecture Truly Means

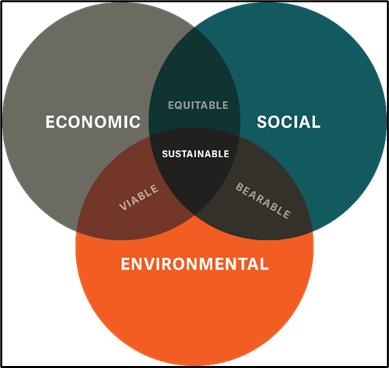

Sustainable architecture is often misunderstood as merely adding solar panels, green roofs or achieving green certifications. In reality, it is a holistic approach—one that balances environmental responsibility, social well-being, and economic viability.

- Environmental responsibility – reducing carbon footprint, conserving resources, and responding to climate

- Social well-being – creating healthy, inclusive, and humane spaces

- Economic viability – ensuring long-term affordability, durability, and value

An architect truly trying to understand sustainability shall ask questions like:

- How does a building respond to its climate and context?

- Does it reduce dependency on artificial energy? Does it promote healthier lifestyles?

- Can it adapt and evolve over time?

Sustainability, at its core, is about thinking long-term, beyond aesthetics, beyond immediate client needs, and beyond short-lived trends.

Sustainability in Practice

Learning from Recent Examples Across the world can help young architects actively contribute to sustainability.

1. Net-Zero and Climate-Responsive Buildings

The rise of net-zero energy buildings marks a significant shift in how we approach design. These buildings aim to generate as much energy as they consume, primarily through passive design strategies combined with renewable energy systems.

A notable example is Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, New Delhi, which integrates high-performance glazing, natural ventilation, solar shading, and rooftop solar panels. Designed to respond to Delhi’s harsh climate, it proves that sustainability and functionality can coexist in large-scale government buildings.

What makes this project significant is not just its technology, but its integration of climate-responsive principles at every stage of design. It demonstrates that sustainability and functionality can coexist—even at the scale of large institutional and government buildings.

The rise of net-zero energy buildings marks a significant shift in how we approach design. These buildings aim to generate as much energy as they consume, primarily through passive design strategies combined with renewable energy systems.

A notable example is Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, New Delhi, which integrates high-performance glazing, natural ventilation, solar shading, and rooftop solar panels. Designed to respond to Delhi’s harsh climate, it proves that sustainability and functionality can coexist in large-scale government buildings.

What makes this project significant is not just its technology, but its integration of climate-responsive principles at every stage of design. It demonstrates that sustainability and functionality can coexist—even at the scale of large institutional and government buildings.

2. Designing with What Already Exists

Demolition and new construction come with a massive environmental cost, largely due to the loss of embodied energy. Adaptive reuse, repurposing existing structures instead of replacing them, has therefore become a critical sustainable strategy.

Across cities, we see warehouses converted into coworking spaces, mills transformed into cultural centers, and heritage buildings adapted into boutique hotels or public institutions. These projects:

Demolition and new construction come with a massive environmental cost, largely due to the loss of embodied energy. Adaptive reuse, repurposing existing structures instead of replacing them, has therefore become a critical sustainable strategy.

Across cities, we see warehouses converted into coworking spaces, mills transformed into cultural centers, and heritage buildings adapted into boutique hotels or public institutions. These projects:

- Reduce construction waste

- Preserve cultural and urban memory

- Save resources and energy

- Add character and identity to cities

Projects like the Mill Owners’ Association Building in Ahmedabad, revitalized for contemporary use, show how historic architecture can remain relevant while responding to modern needs. Adaptive reuse teaches young designers that sustainability is not always about building new, it is often about building wisely with what already exists

3. Sustainable Housing & Community-Centric Design

Housing remains one of the most critical challenges in rapidly urbanizing regions. Recent approaches to low-cost and mass housing increasingly emphasize:

Housing remains one of the most critical challenges in rapidly urbanizing regions. Recent approaches to low-cost and mass housing increasingly emphasize:

- Natural lighting and ventilation

- Climate-sensitive layouts

- Shared courtyards and green spaces

- Walkability and social interaction

One timeless example is Aranya Housing by B.V. Doshi. Decades after its completion, the project continues to inspire contemporary housing models. Its success lies in prioritizing people over form, allowing incremental growth, community ownership, and adaptability over time.

Such projects remind us that sustainability is not only environmental—it is deeply social and human-centered.

Such projects remind us that sustainability is not only environmental—it is deeply social and human-centered.

The Role of Technology and the Young Generation

Young designers bring something invaluable to the sustainability conversation: innovation, curiosity, and adaptability.

Digital tools such as Building Information Modeling (BIM), parametric design, and performance simulations allow designers to test energy efficiency, daylighting, and material impact even before construction begins. Sustainable decision making is no longer intuitive alone, it is data-driven.

At the same time, technology is enabling a renewed appreciation of vernacular wisdom. Elements such as courtyards, jaalis, thick walls, shaded streets, water-sensitive design, and passive cooling techniques are being rediscovered and reinterpreted through a contemporary lens. This synergy between tradition and technology holds immense potential for context-responsive design.

Digital tools such as Building Information Modeling (BIM), parametric design, and performance simulations allow designers to test energy efficiency, daylighting, and material impact even before construction begins. Sustainable decision making is no longer intuitive alone, it is data-driven.

At the same time, technology is enabling a renewed appreciation of vernacular wisdom. Elements such as courtyards, jaalis, thick walls, shaded streets, water-sensitive design, and passive cooling techniques are being rediscovered and reinterpreted through a contemporary lens. This synergy between tradition and technology holds immense potential for context-responsive design.

A Call to the Next Generation

Sustainability is not an optional specialization, it is the present and future of architecture and urban design.

For young architects, planners, designers, and thinkers, the challenge is not to design more, but to design better:

For young architects, planners, designers, and thinkers, the challenge is not to design more, but to design better:

- To question briefs instead of blindly following them

- To rethink materials and construction methods

- To collaborate across disciplines

- To advocate for responsible choices, even when they are not the easiest or cheapest

The built environment can either be part of the climate crisis—or part of its solution. The difference lies in intent. And today, that intent rests firmly in the hands of the next generation